In 1971, Gloria Orenstein received a call from Surrealist artist Leonora Carrington that sparked a lifelong journey into art, ecofeminism and shamanism. Along her journey Gloria befriended women of surrealism who would eventually gain their overdue recognition in art history as pioneers of the Surrealism Art Movement.

The tendency for women artists to be overshadowed by their male partners was particularly fraught for Surrealists. ~Leonora Carrington, 2000.

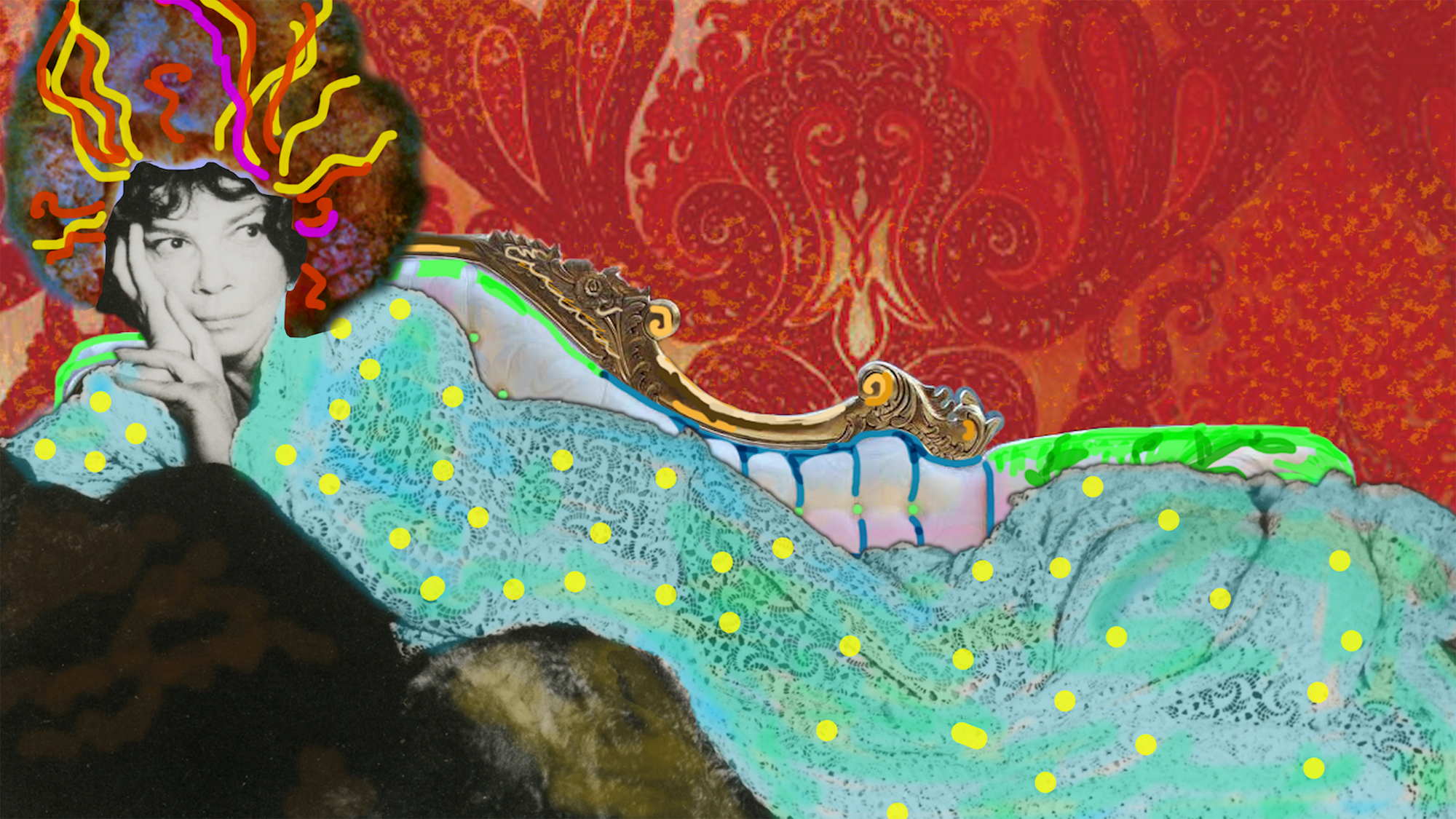

A brief peek at four of the Women of Surrealism you will meet in Gloria’s Call.

Leonora Carrington (6 April 1917 – 25 May 2011) was an English-born Mexican artist, surrealist painter, and novelist. She lived most of her adult life in Mexico City, and was one of the last surviving participants in the Surrealist movement of the 1930s. Carrington was also a founding member of the Women’s Liberation Movement in Mexico during the 1970s. Carrington stated that: “I painted for myself…I never believed anyone would exhibit or buy my work.” She was not interested in the writings of Sigmund Freud, as were other Surrealists in the movement. She instead focused on magical realism and alchemy and used autobiographical detail and symbolism as the subjects of her paintings. Carrington was interested in presenting female sexuality as she experienced it, rather than as that of male surrealists’ characterization of female sexuality. Carrington’s work of the 1940s is focused on the underlying theme of women’s role in the creative process. Her book The Hearing Trumpet deals with aging and the female body. It follows the story of older women who, in the words of Madeleine Cottenet-Hage in her essay “The Body Subversive: Corporeal Imagery in Carrington, Prassinos and Mansour”, seek to destroy the institutions of their imaginative society to usher in a “spirit of sisterhood.” The Hearing Trumpet also criticizes the shaming of the nude female body, and it is believed to be one of the first books to tackle the notion of gender identity in the twenty-first century.

Leonor Fini (1907–1996) was an Argentinian surrealist painter, designer, illustrator, and author, known for her depictions of powerful women. Fini had no formal artistic training, yet she was familiar with the traditional Renaissance and Mannerist styles due to her upbringing in Italy. Surrealist artists in France became very interested in her once she began setting herself up as an artist, and came to know her as important in the movement. She is mentioned in most comprehensive works about surrealism, although some leave her out (and she did not consider herself a surrealist). In 1943, Fini was included in Peggy Guggenheim’s show Exhibition by 31 Women at the Art of This Century gallery in New York. In 1949 Frederick Ashton choreographed a ballet conceptualized by Fini, “Le Rêve de Leonor” (“Leonor’s Dream”). In London, she exhibited at the Kaplan gallery in 1960 and at the Hanover Gallery in 1967. In the summer of 1986 there was a retrospective at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris that drew in more than 5,000 people a day. Many of her paintings featured women in positions of power; an example of this is the painting La Bout du Monde where a female figure is submerged in water up to her breasts with human and animal skulls surrounding her. Fini is considered a great contributor to the feminist movement because her paintings often depict impertinent young women in scenes that empower their image.

Meret Elisabeth Oppenheim (6 October 1913 – 15 November 1985) was a German-born Swiss Surrealist artist and photographer. Oppenheim was a member of the Surrealist movement along with André Breton, Luis Buñuel, Max Ernst, and other writers and visual artists. Besides creating art objects, Oppenheim also famously appeared as a model for photographs by Man Ray, most notably a series of nude shots of her interacting with a printing press. In 1936, Oppenheim had her first solo exhibition in Basel, Switzerland, at the Galerie Schulthess. She continued to contribute to Surrealist exhibitions until 1960. Many of her pieces consisted of everyday objects arranged to allude to female sexuality and feminine exploitation by the opposite sex. Oppenheim’s paintings focused on the same themes. Her abundant strength of character and her self-assurance informed each work she created, conveying a certain comfortable confrontation with life and death. Her originality and audacity established her as a leading figure in the Surrealist movement. Méret Oppenheim’s best known artwork is Object (Le Déjeuner en fourrure) [Object (Breakfast in Fur)] (1936). Oppenheim’s Object consists of a teacup, saucer and spoon that she covered with fur from a Chinese gazelle. The fur represents an affluent woman; the cup, hollow yet round, can evoke female genitalia; the spoon, with its phallic shape, further eroticizes the hairy object. Originally spurred by a conversation Oppenheim had with Pablo Picasso and his lover Dora Maar in café Deux Magots about a fur bracelet she was wearing, Oppenheim created Object to liberate the saucer, spoon, and teacup from their original functions as consumer objects.

Jane Graverol (1905–1984) was a Belgian surrealist painter of French extraction. Jane was born in Ixelles on 18 December 1905 to Alexandre Graverol and Anne-Marie Lagadec. After a traditional education, she enrolled in the Brussels Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in 1921. She began to exhibit her work in 1927. During the last twenty years of her life, she was Gaston Ferdière’s (fr) companion. She died in Fontainebleau on 24 April 1984. Graverol was closely linked to the development of surrealism in Belgium. She would progressively consider her canvases to be “waking, conscious dreams,” and her encounters after the war with René Magritte, Louis Scutenaire, and Paul Nougé, then Marcel Mariën, with whom she collaborated on the periodical Les Lèvres nues, merely reconfirmed her in her beliefs. Her painting La Goutte d’eau is a collective portrait of the Belgian surrealists. She offered an original, dreamy version of “feminine sensibility” in painting, served by a figurative technique that was both precise and cold.